His trademark wit was on display when he gave this speech explaining how he figured out that missing atheist Madalyn Murray O’Hair was not dining on bonbons in New Zealand, as police theorized, but had actually been brutally murdered.

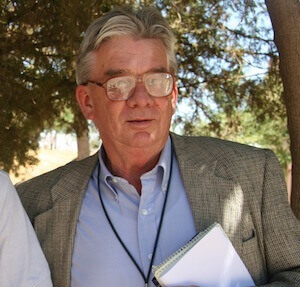

Last year, MacCormack and Express-News Photographer Jerry Lara spent months documenting the toll of violence from the Mexican drug war, and how life on the Texas border has dramatically changed for the worse. The result was a compelling series of articles and photos called Mexico in Crisis. MacCormack won an award for his work this month from the Inter American Press Association.

Given MacCormack’s gift of gab and skill at reporting, I thought it’d be entertaining and educational to do a Q&A with him, and learn how he and Jerry worked on the stories.

I was right.

Q: How did the series come about?

A: Well, it’s sort of a self-serving answer. But back in the middle of last summer, the lords were casting about for big ideas, big projects. And I told —

The lords being the editors.

Yeah, the editors. The editors were casting about for big stories, big ideas. And I said to [Express-News Projects Editor David] Sheppard, ‘As far as I’m concerned, the biggest story in Texas is what’s going on on the border in Mexico as well as how it’s affecting the changes on the Texas border.’ And he said, ‘That sounds right to me.’ The real push was when [Executive Editor Bob] Rivard was 100 percent behind it. If you’ve got the top dog behind you, you’re going to do things and things will happen.

The project didn’t really start out as a project per se. It gained momentum. The first thing Jerry Lara and I did was, we went to Juárez for the grito, which is the celebration of Mexican Independence. It was such a powerful story because the mayor of Juárez had to give it to an empty plaza. The whole city was bunkered down. And while we were there, some poor journalist for El Diaro was shot, whom we had just talked to. There was tremendously compelling material there.

Jerry Lara was the photographer who was with you the whole time.

[pullquote]

The thing about working in Mexico right now on the border is you have no way to calculate the risk.

[/pullquote]Yeah, Jerry Lara was the photographer throughout the whole series. He’s one of the finest journalists I’ve worked with. I don’t mean just photographers. I mean journalists. He and I were back to back, side by side. He had my back because he had a much better antenna for danger in Mexico than I did, because I’m a gringo from New York, you know?

Were there some dicey situations you had to deal with?

Well, the thing about working in Mexico right now on the border is you have no way to calculate the risk. I mean, we were in Juárez three times, we were in Monterrey, we were in Nuevo Laredo, we were in Matamoros, and we were in Progreso. And in every place people were being killed. But we had no way to calculate risk. So we just tried to be careful but not timid. And I had no idea whether I faced any danger at any point. But I know we were in many, many dangerous areas. On one occasion, we were in a bad neighborhood in Monterrey. And (Jerry) just said, ‘Look, I don’t like the looks of this. Let’s get out of here.’ And we left. We didn’t like squeal out or anything, we just got out of the neighborhood. Later we talked to the reporters for El Norte, and they said, ‘Man, we don’t go there. That’s a bad neighborhood.’ So Jerry was the guy with the antenna, the guy who could basically sense whether or not we were in danger. I’m bolder than he is, mostly because I’m more clueless.

What happened to the journalists you mentioned who got shot?

Well, we were in Juárez and we went to the plaza right by the cathedral. This was in September of last year. And we were just shooting color basically. We didn’t have anything specific in mind. And we ran into two photographers from El Diario. And they were young guys. Real young. And we could see they were photographers because they had the gafetes, which are the things you hang on your neck, and they had the cameras. So we all yucked it up and shook hands. You know, colleagues.

And then two hours later, we responded to a shooting at the mall. And those two guys had been shot up driving through the mall parking lot. One was killed and one got three bullets in him. And to this day I have no idea why they were attacked. We later learned that the plaza was a really dicey area because there’s a lot of street-level drug sales there. The local press had been warned to stay away from there. Long and short, the guy was killed and we had just talked to him two hours earlier. So it’s a very dangerous place but there’s no way to really calculate the risk.

What was your goal with the series of stories?

[pullquote]

It’s the most improbable, most violent, and most inexplicable thing going on in the world right now, in my opinion.

[/pullquote]There were two goals really. Having lived in Texas for 25 years — and crossing the Mexico border into every border city, from Juárez all the way to Matamoros, and remembering how it was 25 years ago, when you could just come and go and people lived their lives on both sides of the border, and the security was very low-key, there was no danger whatsoever — one of the goals was to document how dramatically the border has changed. And what was once a very soft border is now a very hard border. No longer do people go back and forth. And this whole way of life is essentially over. The whole tourist industry in northern Mexico has collapsed. The tourist markets virtually don’t exist any more. People who live in Brownsville, most of them fear going to Matamoros. And that’s the whole pattern. So that was the first goal.

Related: How to contact an investigative reporter

The second goal was, I was looking at this drug warfare in Mexico. And hundreds of people were dying. And I thought to myself, how could you not want to go chronicle this, write about it? Because it’s the most improbable, most violent, and most inexplicable thing going on in the world right now, in my opinion. We owed it to the Mexicans who live on the border. We owed it to our readers to go write about the drug violence. So there were kind of two themes: The border life is over as we knew it, and northern Mexico is collapsing into complete anarchy.

You also write about how the severity and nuances of the violence in Mexico varies from city to city. It’s different in Monterrey compared to Juárez, for example.

Yeah. In Juárez, for example, the press can function. The press still has somewhat autonomy. In Matamoros, the press is totally under the heel of the gangsters. They don’t dare write anything. In Monterrey, it’s 90 percent free. So if you use the press as an indicator, it’s very different in all three areas.

When we went to Monterrey, it was a big, bustling, modern, rich place. There was some violence but essentially normal life went on every day. When we went to Juárez, it wasn’t a ghost town, but tens of thousands if not more people have left. All the commerce was down, businesses had burned, closed. The place was like a shadow of what it had been. I didn’t spend much time in Matamoros. It’s probably the least stable place of all. It was like in a coma, you know? Every place is different. We’re not experts on this, we just kind of took snapshots.

Well, you told readers what you saw. Going back to the example of the grito, it was a pretty good example of how reporters can show, don’t tell. The scene and details tell the story.

Yeah, they can have all the generals they want on the balcony and they look good on TV. But when you’re standing with the mayor on the balcony, you’re looking out onto emptiness, you know? There’s soldiers, there’s cops, there’s blue and red lights, but there’s nobody down there. It’s like they’re holding it in a city that’s been evacuated, you know?

It tells the story right there.

It was a great photograph.

You mentioned the media, and you wrote how difficult it is for journalists down there to navigate what’s acceptable coverage and what’s not.

And it varies city by city.

How much of that did you know going in and what surprised you?

[pullquote]

The journalists are trying to work right up to the line of getting killed.

[/pullquote]I had a pretty good idea because I’ve known journalists in most of these cities for many years. It wasn’t like I’ve never gone to Matamoros and it wasn’t like I didn’t have press sources there. So before I went and visited, I talked to people. I had a general idea.

But what shocked me, what really made a big impression on me, is how in every place, the journalists are trying to work right up to the line of getting killed. In Juárez, they are much more aggressive, but there are certain things they can’t do. So they write right up to the line. In Matamoros, for example, they can do virtually nothing. But this one guy, he’s an editor at a big paper, he and I had this long talk. And he said, ‘You know, it’s absolutely controlled by the narcos. They tell you what to publish, what not to publish. We’re totally under their thumb.’

And I said, ‘Well, why are you talking to me?’ He said something to the effect of, ‘I want to preserve the little bit of the journalist that’s still in me.’ So I was just impressed by how in every circumstance, they worked right up to the point where their lives were in danger. And because it’s a fuzzy line, they never really knew. And so you could cross the line unknowingly, and you get killed.

They don’t feel sorry for themselves. I was scolded after I wrote that long piece about journalism in Mexico by an editor down there. He said, ‘Man, you forgot to tell all we are doing. You made it sound like we’re all up a tree with guns pointed at us. But every day we navigate this and we figure out what we can publish.’ He said, ‘You really forgot to say what we are doing, because you spent so much time saying what we can’t do.’

How do these media blackouts affect the Mexican public?

It’s a tool of the criminal element to assert control over society. If the press is completely intimidated, and the public has to rely on Twitter and not very mainstream sources for information, it furthers the societal breakdown. I mean, if you can wake up in the morning and read the paper and it tells you what happened yesterday, even if there are bombs dropping, you fell like you still more or less have a sense of reality.

But if you wake up in the morning, and you know there was giant shoot out in the plaza, but the story’s about some guy who got pulled over because he hit a horse, you’re entering a realm that’s unreal. It makes you feel more vulnerable. It’s a furtherance of societal breakdown.

Related: Top five books every student journalist should own right now

Essentially, the (northern) third of Mexico is out of control of the government. I mean, they send the Army in, they send the Navy in, there’s shoot ’em ups, they kill narcos. But this part of Mexico is operating beyond the control of the federal or the state governments. When you have a city like Monterrey, which is the equivalent of Dallas — it’s a huge city, it’s prosperous. But in the last couple months the violence has gotten worse there. And it’s simply because the criminal elements are so powerful that the state and federal governments and municipal governments, they can’t defeat them.

It’s impossible for an American to grasp this. It’s like the Russian gangs are running Long Island. Or the street gangs are running L.A. Or they don’t yield to the civil authorities. We have no concept of this. We live in a society where law and order is the rule. Systems work. There’s a justice system. They have none of that. The impunity level in Mexico is in the upper 90 percent. You shoot someone and kill ’em, the chance of getting arrested and convicted is about as remote as getting hit by Hailey’s Comet. There’s total impunity. It’s really a nationwide crisis. And I don’t think most of us in the U.S. grasp this. I don’t think most Americans grasp how bad it is.

What’s the way out? What’s the solution?

[pullquote]

It’s a rare thing to get commitment for travel and space and also the kind of green light to follow your own nose. It’s a wonderful thing if you’re a journalist.

[/pullquote]What’s the way out? The only way out is to somehow fortify and create public institutions, police, justice, court systems, electoral systems, which are strong and are clean and are competent. And they don’t have that in most instances.

The U.S. is, of course, a big part of the problem. There’s 20 or 25 billion dollars flowing into Mexico annually to pay for the illegal drugs here. That’s where the cartels get their strength. It’s a multi-national problem.

How much time did you spend on the series?

Basically four months. In four months, we went to seven or eight places.

It was very, very rewarding. It’s a rare thing to get commitment for travel and space and also the kind of green light to follow your own nose. It’s a wonderful thing if you’re a journalist. Without being a suck up, if I didn’t have the editors, I wouldn’t have been able to do it.

Yeah, there’s a lot of expense involved in that.

Yeah. But it wasn’t even so much the expense. So we went to Juárez two or three times. We went to Monterrey. There’s not really a lot of money involved. The commitment is for the space in the paper. We had a lot of double trucks. I think my stories got cut a little bit. But when push came to shove, we always got the space. That was because the boss was behind it.

And it was readable and the pictures were really compelling. That probably helped.

It was a two-man show throughout. you can’t go to Mexico by yourself and do this kind of work. You better go with someone who you trust and knows the lay of the land.

When you sat down to write this, what was going through your mind? You’re down there in another country but you’re writing for people in the United States.

Well, I have a lot of respect for my readers. It was written one (story) after the other. For seven or eight stories. You’d go on a trip, spend a week or four days or five days somewhere. You come back. And then you’ve already done a lot of phone reporting. And then you turn that one around. You write it in two or three days. And then you get on the plane again. It was like covering — not a breaking story — but an evolving story. You go from one place to the other. It was fast-paced.

I don’t get writer’s cramp or anything like that or stage fright. So it was really, really fun. There were like two phases of it that were fun. The reporting phase was really fun. Because you’re in a strange place. You gotta come back with the goods. You don’t know what you’re doing. You fly to Monterrey, you have a few sources, but you really don’t know what you’re going to do. So you’re thinking on your feet the whole time.

[pullquote]

We have no concept of this. We live in a society where law and order is the rule. Systems work. There’s a justice system. They have none of that.

[/pullquote]One of my better ideas was to call a psychiatrist in Monterrey. And I said to him, ‘Tell me what it’s like.’ And he was a fabulous source. I had been sitting in my hotel room thinking, ‘I don’t have enough, I need something to really capture this.’ And I went to the yellow pages of the phone book and started calling shrinks. Most of them thought I was a nut. I’m literally calling Mexican shrinks with my bad Spanish, and I’m saying, ‘I’m an American reporter, I’m writing a story, I’m wondering if you can talk to me about what the effect is on the general public of the violence.’ And one guy said, ‘Yeah, come on over.’ He was brilliant in his analysis.

To get back to what I’m trying to say, there are two phases. There’s the reporting phase where you really don’t know what you’re going to get. And there’s a certain amount of tension because you’re looking and you’re searching and you’re working long hours. And you’re looking for the story that’s out there somewhere.

And then you get back and then you start looking again for the story that you have in all your notes. And that’s a very tense, exciting thing to try to find the story. Because you know you have tons of great information. And then there’s that process that only writers can grasp where you’re sitting down with a mess of information. Your brain’s full. Your notebooks are full. And you got ten times more than you know you can use. But you have to come up with a very clear and compelling and truthful story. And that’s an experience and an adventure in itself.

And it’s satisfying when that picture starts to emerge.

Oh, yeah. It’s totally rewarding. It’s a lot of fun.

Well, great job, man, thanks so much.

Well, thank you. Good luck getting this down to something you can use.

This was so interesting! Thank you so much to you both for sharing.

RT @John_Tedesco: Mexico in Crisis: Q&A with @JohnMacCormack. “The journalists are trying to work right up to the line of getting killed …