“The Most Hated Woman in America” is a new Netflix movie about Madalyn Murray O’Hair, an outspoken atheist who mysteriously went missing in Austin in 1995 — along with $600,000.

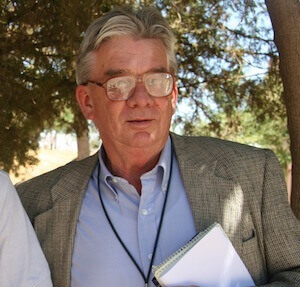

No one knew what happened to her. And it’s likely no one ever would if it hadn’t been for a series of investigative articles written by San Antonio Express-News reporter John MacCormack, who realized it was a murder case before the police.

Director Tommy O’Haver said the reporter in the movie is a fictional composite of MacCormack named Jack Ferguson, played by Adam Scott.

Without seeing the movie, I think it’s safe to say the truth about the reporting is going to be more interesting than fiction. Here’s a video and transcript of my interview with MacCormack as he looked back on the O’Hair story:

Who was Madalyn Murray O’Hair?

Madalyn Murray O’Hair was a formerly famous atheist who had achieved prominence in the early 60s when she filed a lawsuit alleging that school prayer and school bible reading was unconstitutional. It was one of three suits filed in a short time frame in the early ’60s. Hers was the third. They all three made the same legal claims. And the Supreme Court decided in favor of each one of them. However, O’Hair came out of all this identified as being the one who had filed the most important suit and she took advantage of it and basically became a professional atheist. And she appeared on talk shows, she established various atheist organizations, eventually settling in Austin. And she was quite prominent in the ’60s and ’70s.

In 1995, O’Hair, her son and her granddaughter disappeared. How did you get involved in the story?

The assignment was a casual mention by my then-boss, Fred Bonavita, the state editor, that it had been a year since Madalyn Murray O’Hair had disappeared and why didn’t I check into things and see how the case was going? I, frankly, wasn’t even aware that she had disappeared because there was no commotion made, no police complaints filed, nothing when she disappeared. The organization just kept it very, very mum. So I didn’t know she was gone and I knew very little about her at that time.

How many stories did you write?

Well, there were about 80 to 100 stories over three years and about five of them really mattered. The first one was just laying out that she was gone. And I met a few critical sources who would help me later. But it didn’t go very far. And no one had any idea whether she had fled to the South Seas with atheist money or whether she had been captured by the Christists or the CIA or the Vatican as various theories were floating around.

In November of 1996, I looked at the 990 (tax) forms filed by several of her atheist organizations. And they revealed that some $600,000 had disappeared at about the same time as the O’Hairs had disappeared. So when you add a lot of money into the plot of disappeared persons it gets more interesting.

What were the major breakthroughs?

The next big development was that I was approached by a private investigator named Tim Young who proposed that we collaborate because his specialty was finding people who didn’t want to be found. And he frankly thought it would be rather easy to find them. …

[pullquote]

The most critical breakthrough for us came in June of 1998 when I got an anonymous call from someone who basically told me that the O’Hairs had been killed and that another party named Danny Fry had disappeared with them.

[/pullquote]The most critical breakthrough for us came in June of 1998 when I got an anonymous call from someone who basically told me that the O’Hairs had been killed and that another party named Danny Fry had disappeared with them. By this time we were pretty much working the theory that they were dead because Tim Young hadn’t been able to find no sign of life anywhere on the globe. So with the introduction of Danny Fry — who was kind of an alcoholic low-life con man from Florida — into the plot, and the fact that he had disappeared, this really made things more interesting.

Related: How a journalist solved the murder case of the ‘most hated woman in America’

It was in this phone call that we were told to pay attention to a guy named David Waters, who was an ex-con who had worked for the O’Hairs a few years earlier, had stolen about $50,000 from them, and O’Hair had pressed the case against Waters, and he had been convicted. And she had also devoted an entire issue of the American Atheist newsletter to David Waters and his horrific, shameful past. Because he had done some very, very bad things in his past. Including being convicted of murder.

So now we had a murderer, we had four disappeared people, we had $600,000 gone somewhere. So it was beginning to get much more serious for Tim Young and I.

In August of 1998, Tim Young and I had a split. He felt it was his duty as a private investigator to go to the police with the information we had. Because we had a pretty coherent theory now. And I had no confidence in the police. I’m speaking of the Austin police, who had pretty much ignored the case. They treated it as a voluntary disappearance by a person, which isn’t a crime. So Tim and I had a — not acrimonious — but it was an unfriendly split. I decided I was going to keep reporting. He went to the Austin police. They ignored him. And from then on I worked alone.

How did you find out Danny Fry had been killed?

In October of ’98, I happened across a small story that was generated by AP in Dallas, based on a (Dallas) Morning News story about the third anniversary of the discovery of a nude, headless, handless body beside the Trinity River. It had been found in October of ’95. And I just, somehow, fortunately thought to myself, ‘That’s the same weekend that Danny Fry disappeared, and you know, why not?’

[pullquote]

This really inspired the FBI to get involved. So they threw a lot of manpower at it. And within a couple of months, they’d arrested David Waters, and they’d arrested a second ex-con named Gary Karr, who was a real cold-blooded snake.

[/pullquote]To make a long story short, I tried to exclude Danny Fry from being that person. … Nothing could exclude him. So I called the sheriff’s office in Dallas County and I said, ‘Look, I might know who your missing guy is.’ And they’d invested hundreds of hours and hundreds of missing person’s reports trying to find out who this was. So they were kind of cautious about talking to me but they wanted to do it. So I flew up there. We all sat in a little room. And I walked them through the O’Hair disappearance. And to them it was like science fiction. But eventually they came to see that there was a possibility that this headless, handless guy might be my Danny Fry who had disappeared in Texas after coming from Florida. So that was a big, big development. They didn’t laugh me off or anything, they took me seriously.

Danny Fry’s relatives weren’t the type who were comfortable with police. So I got three of his relatives to contribute blood samples, and the lab tested it all, and voila, in January of ’99, it turns out that the headless, handless body was Danny Fry. And that pretty much closed the door on the O’Hairs being alive anywhere.

So I wrote another story basically laying out the picture of them being taken to San Antonio, Danny Fry’s with the O’Hairs, he’s making calls from the same places that they’re known to be. And he’s dead. So, ergo, they’re likely dead. And this really inspired the FBI to get involved. So they threw a lot of manpower at it. And within a couple of months, they’d arrested David Waters, and they’d arrested a second ex-con named Gary Karr, who was a real cold-blooded snake. So the FBI got involved hardcore and then the story proceeded from there.

At this point, the only thing that was really missing, the critical component, was proof of their deaths. It’s hard to prosecute someone for murder when you don’t have a body. So that hung over the case for a long time. No one knew where the bodies were.

How did authorities find out where the bodies were?

David Waters decided, basically, it was over. He was in state custody on a state offense. And he made a deal with the feds that if they put him in federal prison, which apparently is a lot nicer place than state prison, that he would cooperate. And that was the deal they cut. So Waters gave a very long statement describing everything, and eventually also walked them out there and said, ‘There’s the spot.’ And they dug and they found the bodies. … They kind of knew they found Madalyn Murray O’Hair when the turned up a titanium, artificial hip. And the DNA tests proved that these were the bodies of the three O’Hairs plus Danny Fry’s head and hands all buried in the same hole. And that kind of brought things to an end.

What’s it like as a reporter solving a murder mystery?

Well, as a newspaper reporter, most stories are short-lived and you never really figure everything out. And it ends up, you know, you’re just further into the murk. With this story, it went on for three years. I wrote 80 to 100 stories. And it kept getting better and better and better the longer we pushed and searched. Not every day. There were long periods of no progress. But at the end of the day we managed to take a complete mystery, everything was confused, and we pulled it all the way into the sunlight where you had a clear idea, a clear story of what happened. And it solved a very complex murder case, which doesn’t happen every day. So it was very satisfying. But I don’t confuse it with more important reporting about social issues. This was just a whodunit that was just a hell of a lot of fun to report, a lot of work and at the end of the day, very satisfying.